To put slave jails in perspective, there are a few other terms I’ll need to explain; breeding farms, Partus Sequitur Ventrem, coffles, Lumpkin’s Alley, the African burial ground, and slave rings. I’ll provide an example to put it all in context. Robert Lumpkin bought three lots in Richmond, VA in 1844 that would become America’s most infamous slave jail, nicknamed “The Devil’s Half-Acre.” It was already a holding facility for slaves but Lumpkin took it to a brand new level.

Richmond was at one the second largest center in America for the sale of slaves, trailing only New Orleans. Virginia had a surplus of slaves due to a decline in tobacco production and the practice of slave breeding. Unlike Charleston, SC which was the largest center for receiving African slaves. Virginia (along with Maryland) was dedicated to the breeding of slaves. The forced, continual mating of slaves for the purpose of bearing children that could later be sold.

Many of these children were America’s attempt at eugenics, an attempt it rarely talks about. If it comes up at all in history books, it describes laws preventing the “enfeebled” from marrying and sterilization of the poor, immoral, and disabled. They don’t mention the breeding of the biggest, strongest black “bucks” with the perceived best breeders. Colonial Americans broke with the British tradition where children followed the father’s heritage. They instead implemented, Partus Sequitur Ventrem under which children born to slaves would be what the mother was; ensuring that children of slaves would also be slaves. Not gaining their freedom as in other forms of servitude and slavery in most parts of the world. The same law established that white men could not be found to have raped their slaves.

Virginia slaveowners would bring their excess slaves to the Richmond slave markets for sale to Southern plantations. At the same time, agents of the largest traders would solicit individual farms and plantations; offering to sell their slaves for them. Farmers that had failed to properly rotate their crops were experiencing low yields and the sale of their often inherited slaves was like found money. After their purchase at the slave market, they were housed in slave jails. Although Lumpkin was the largest of the jailers in Richmond, there were multiple slave jails in the same area; similar to seeing multiple bail-bondsmen in the same neighborhood, close to a nearby jail. In what was called, “Lumpkin’s Alley,” multiple slave jails were located. All just a few blocks from the present-day capitol building. Multiple slave jails were often located near the large slave markets with Lumpkin’s Alley being an example.

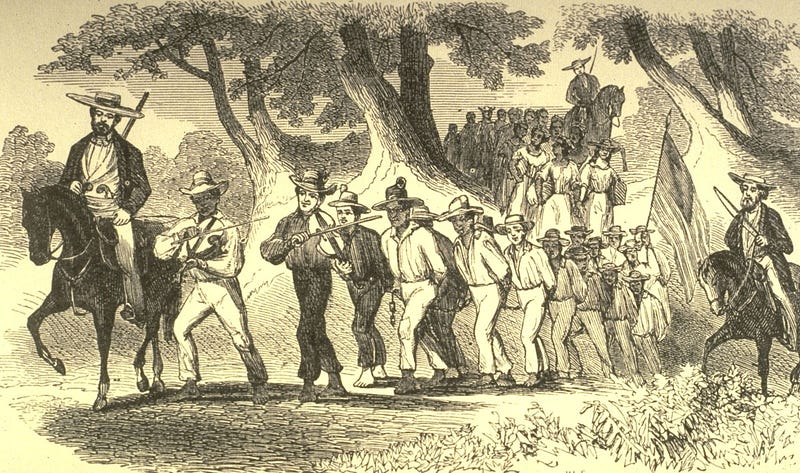

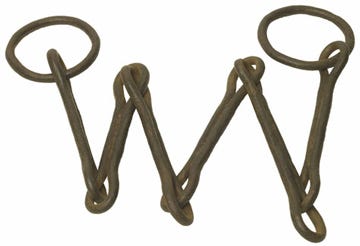

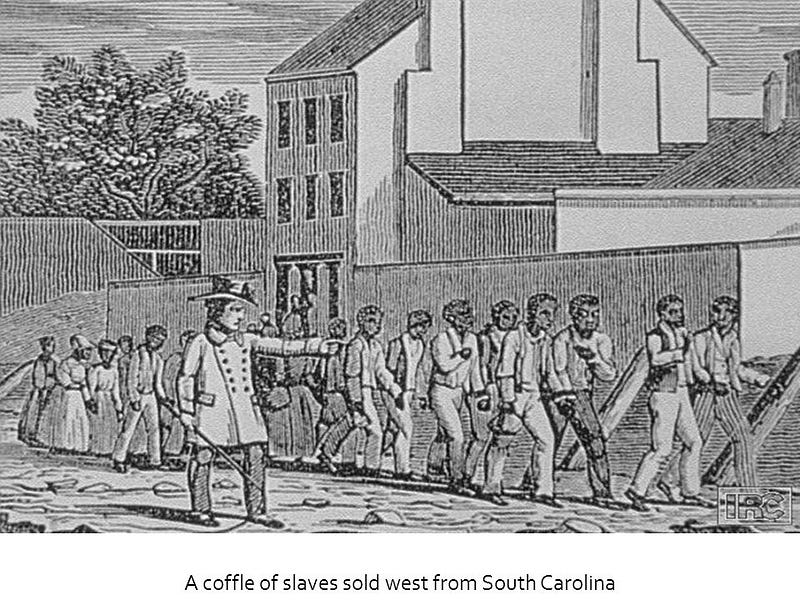

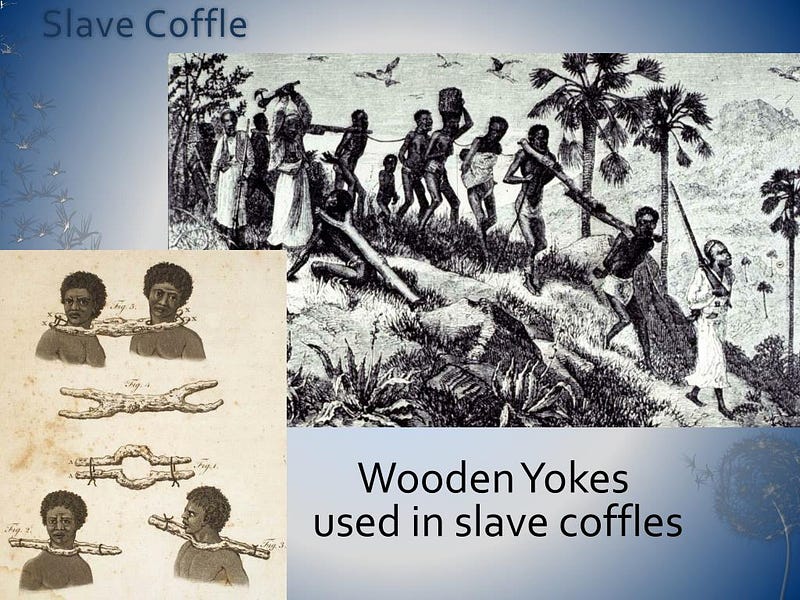

Today, Richmond has multiple train lines running through it but they didn’t exist in the early days of organized slave trading. Slaves headed to Florida, or New Orleans might be sent by boat. Slaves headed West or Southwest had to walk. Some to what is now West Virginia where they could catch a boat. Others to points as far away as Georgia and Alabama. Slaves were paired together with iron rings around their necks, fastened with an iron or wooden bar, then chained to the other slaves in what was called a “coffle.” The jails would hold the slaves until there were enough to make the trip worthwhile. Coffles were herded by men on horseback with whips, guns… and dogs. After a time, railroads were built (primarily by slaves) and coffles diminished, not to to the humanity of the slaveowners but because a more productive method was found.

Back to Robert Lumpkin’s jail, and how it earned its nickname; the Devil’s Half-Acre. It wasn’t because Lumpkin was the largest slave trader in the area for over twenty years, although he was. It was because of the harsh conditions and Lumpkin’s cruelty. You may have seen images of how slaves were packed into slave ships for the Middle Passage. Lumpkin did something similar but on dry land. Slaves were packed sometimes literally atop one another in a cramped space with no toilets and almost no access to the outside. Many slaves died of sickness and starvation; others from beatings and torture. The dead were cast into mass graves and barely covered. This area was called the African burial ground and can be found today by those knowing to look. Lumpkin’s Jail reeked of dead bodies, human excrement, sweat, and smoke; its nickname, the Devil’s Half-Acre is well deserved.

Modern-day Richmond (like many Southern cities) is struggling with how to commemorate its history. Corporate and government leaders are trying to preserve the past while keeping it from sounding harsh. Some of the same people are struggling with their Confederate statues. There had been some talk of “not using Lumpkin’s name and making him famous again.” No such concern exists for the Confederate Generals who still line Richmond streets. Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, and Stonewall Jackson have permanent places on Richmond’s Monument Avenue, forbidden by a new law from being removed.

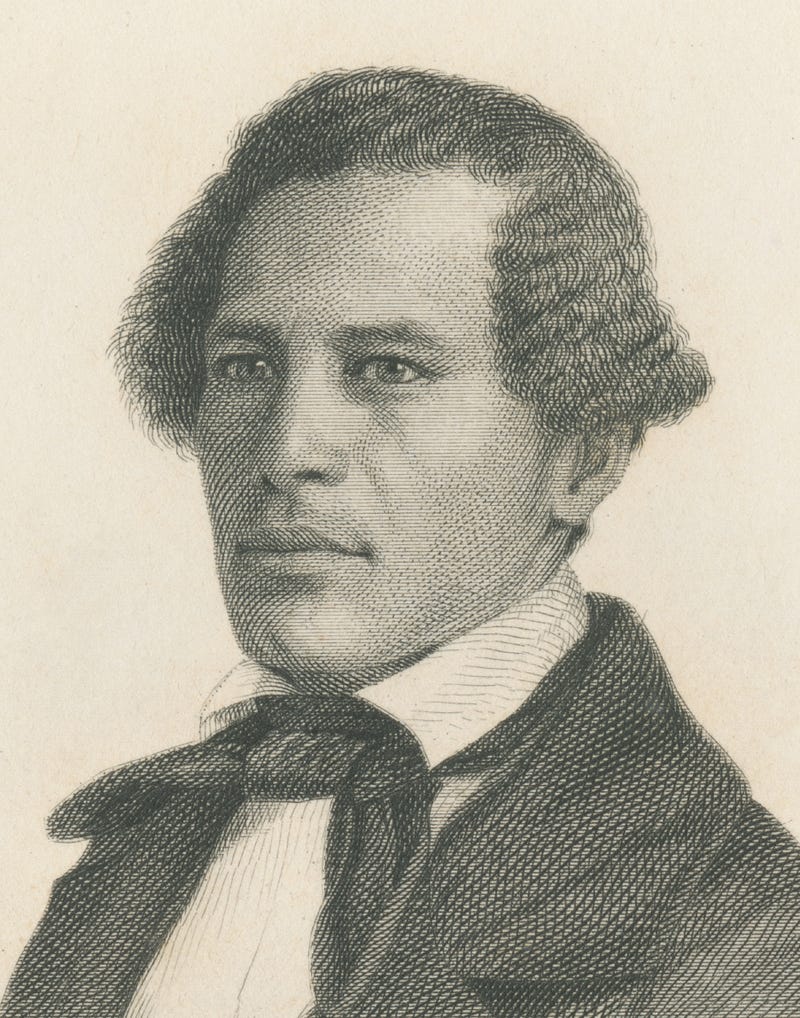

Lumpkin bought a light-skinned slave girl named Mary at age twelve. She bore five children by him and at some time they married. He sent his even lighter-skinned daughters to fine schools; ensuring they got the best education available. All while he maintained a “whipping room” where slaves laid on the floor, bound at their ankles and wrists, and were beaten; sometimes until dead. I give Lumpkin no credit for his slave wife. He ran with a crew of other slavers who also married their slaves who bore them children. Before the Civil War ended, Lumpkin sent Mary and their children to Pennsylvania where they couldn’t be sold back into slavery to pay his debts. When Lumpkin died, she inherited his land which she ultimately sold to a Baptist minister, Nathaniel Colver, looking to establish an all-Black seminary. That site later became Virginia Union University.

Though Lumpkin’s jail was the largest in Virginia. One company, Franklin & Armfield, applied modern business practices to slave trading. They had multiple slave-depots (jails) along their various routes. If you pictured these jails as regional warehouses from which they shipped their goods across the South; you’d be on the right track, They utilized all manner of transportation, although the unlucky slaves headed to Atlanta, walked the whole way. Coffles followed the Cumberland Road to Wheeling, VA (now West Virginia) and the Ohio River where they boarded steamboats. On other routes, they might reach a train station and be packed in cars until they reached their destination. After Isaac Franklin and John Armfield got rich dealing in human misery, they retired and became socially prominent members of their prospective societies.

Temporary slave jails were also a fixture of the slave markets. Filled to the brim at the beginning of the day of each sale. Gradually emptied until all the slaves had been sold. The evidence of the largest slave markets in Richmond, VA, New Orleans, LA, and Natchez, MS has all but been erased. Efforts to memorialize those sites have mostly failed or been sanitized so as not to expose current visitors to a “better forgotten” past. From my home in Orlando, the nearest large slave market I could discover is in Saint Augustine, two hours away. Though its existence was well documented, some chose to deny it was used for that purpose. Even in 1914, embarrassed locals refuted their history.

“I have seen the legend of the old slave market. I want to state that this is a fabrication, to pander to the morbid tastes of a certain class that come or came down to our section with the hope and desire to see only the revolting and objectional side of the picture. This market when I knew it stood near the plaza if my memory serves me, and only fish meats and vegetables were sold there.” — J. Gardner

If you live in the South, you’ll likely be more successful tracing slave markets. Once you locate those, rest assured there was an accompanying slave jail, even if temporary. American history can only be learned from if all of its aspects are fully and accurately represented with slave jails being a part of the story.